Fun and easy science experiments for kids and adults.

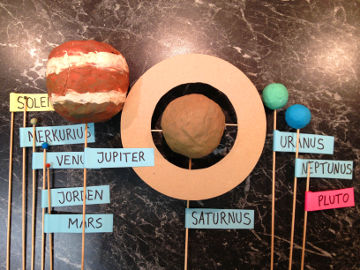

Astronomy

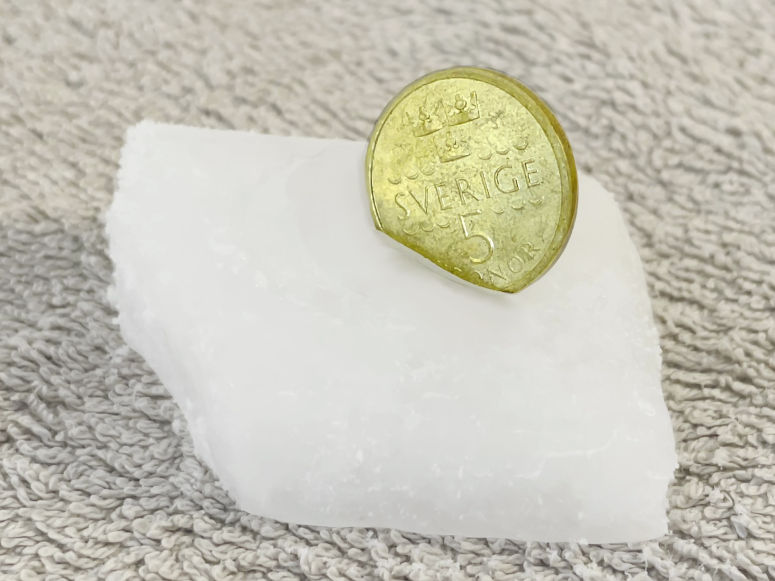

Tiny meteorites are everywhere around us. In this experiment about the solar system you will try to find them.

| Gilla: | Dela: | |

Materials

- 1 large bucket

- 1 plastic bag

- 1 spoon

- 2 white papers

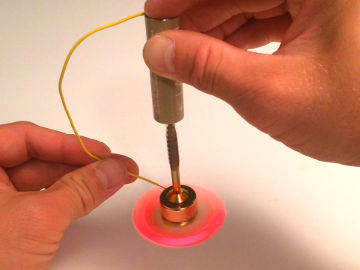

- 1 neodymium magnet (a regular magnet also works, but not as well)

- 1 microscope (if you have one)

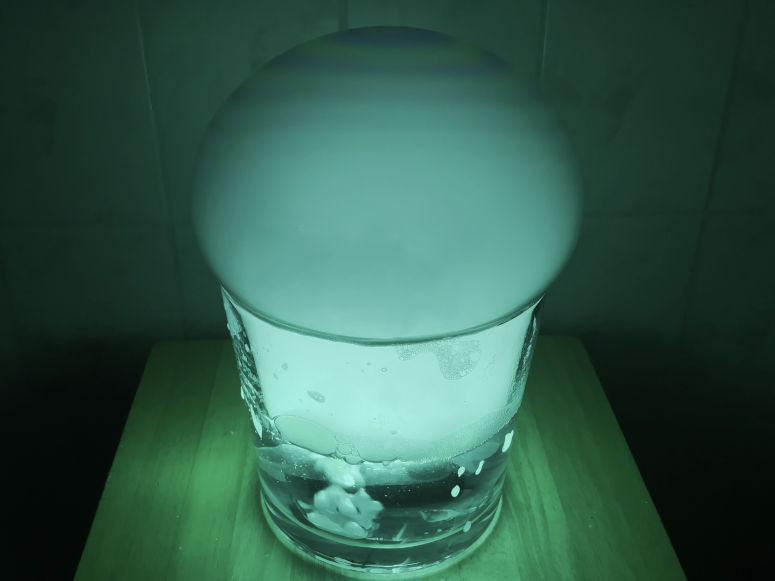

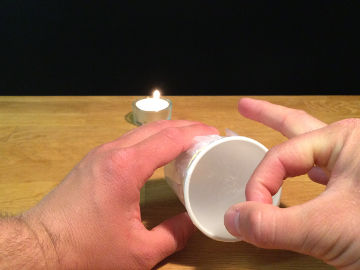

Step 1 (alternativ A)

Step 1 (alternativ B)

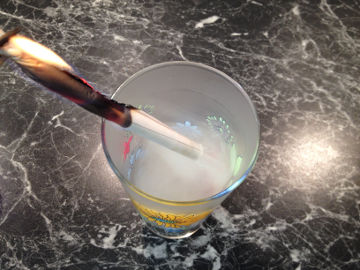

Step 2

Step 3

Step 4

Step 5

Short explanation

There is a small chance that some of the particles you have found are micrometeorites from space. Many of these are magnetic, and if you have a microscope, you can also see that they are often globular with small craters in them. But unfortunately - even if you find a particle that matches this description, the chances are much greater that it's of terrestrial origin. But those are also cool.Long explanation

Every day, Earth is bombarded with dust and rocks from space. Most large rocks are gasified in the atmosphere, but some small particles reach Earth's surface.Space dust are particles weighing between 10-9 and 10-4 g (0.001 and 100 µg). Scientists have estimated that between 10 000 and 50 000 metric tonnes (22 000 000 and 110 000 000 pounds) of space dust hit Earth's atmosphere each year. Of this space dust, less than 10 % is estimated to reach Earth's surface. These estimates mean that every square metre (11 square feet) of Earth's surface is hit by between 2.5 and 8.0 µg of space dust each year. This can be compared with the fact that the same area of Earth's surface is estimated to be hit by around 0.98 µg of meteorites (the micrometeorites' larger siblings) each year. So space dust is much more common than meteorites. Out of the space dust that hits Earth's surface, the larger particles, those between 0.05 and 2 mm in diameter, are called micrometeorites. Micrometeorites around 0.2 mm in diameter are most common, and they weigh arout 15 µg. Unfortunately, all these numbers lead to the conclusion that the chance that you will find a micrometeorite is small. If one assumes that all space dust that hits Earth is micrometeorites and 0.2 mm in diameter, every square meter (11 square feet) of Earth's surface is hit by such a micrometeorite once every three years. If you use a microscope, and are meticulous, you will probably find spherical and magnetic particles. A small percentage of these may be from space, but most come from Earth instead, which is also interesting. For example, these particles are formed by metal grinding and can be transported far into the atmosphere. How to distinguish a micrometeorite from terrestrial particles is very difficult, and I'm not good enough at it to give you any useful tips. You can try simply googling images on micrometeorites and comparing. When scientists collect micrometeorites, they don't look in gutters but in places that have not been affected by humans, for example in sediments in the sea or in glaciers in Antarctica. Roofs are excellent collectors for micrometeorites. They have large areas and stand high above the ground from where dust and other things are stirred up. When it rains, the micrometeorites are flushed off the roofs and down through the downspouts. Micrometeorites can consist of metal, stone or both. The most common metal in micrometeorites is iron, and it's these micrometeorites that you can collect using this method.

Experiment

You can turn this demonstration into an experiment. This will make it a better science project. To do that, try answering one of the following questions. The answer to the question will be your hypothesis. Then test the hypothesis by doing the experiment.- Where can you find the most micrometeorites?

- What is the best method to collect micrometeorites?

| Gilla: | Dela: | |

Similar

Latest

Content of website

© The Experiment Archive. Fun and easy science experiments for kids and adults. In biology, chemistry, physics, earth science, astronomy, technology, fire, air and water. To do in preschool, school, after school and at home. Also science fair projects and a teacher's guide.

To the top

© The Experiment Archive. Fun and easy science experiments for kids and adults. In biology, chemistry, physics, earth science, astronomy, technology, fire, air and water. To do in preschool, school, after school and at home. Also science fair projects and a teacher's guide.

To the top